It’s no secret to anyone who knows me - that I love history. I love to read about it and write about it. I think that history gives us our foundation and insights to who we are as a nation.

I have always had a special interest in World War II for some reason. Maybe it’s a reincarnation thing and I lived another life during that era. What ever the reason, I was especially fascinated during the years that I lived in Germany and visited the landmark sites where so much of that war had occurred.

I usually like to end the show with information on women in history, but given what a historic day this is, I decided to switch things up and open the show with women in history.

December 7th is Pearl Harbor Day. As President Roosevelt called it, “A day that would live in infamy”. On December 7, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor Hawaii. the attack started at 7:48 a.m. Hawaiian Time. 90 minutes after the attack began, it was over. And 2,386 Americans were dead and 1,139 had been wounded. It was equivalent to 9/11. Unexpected and devastating.

Lt. Annie G. Fox served as the chief nurse in the Army Nurse Corps at Hickam Field during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

And she was the first woman in history to receive the Purple Heart for combat service for her role in coordinating treatment of the wounded that day.

It was the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II.

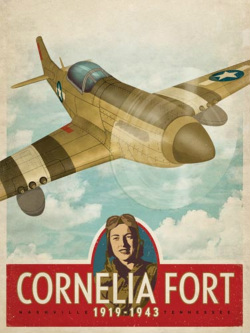

But there was also another woman who was at Pearl Harbor on that infamous day. A pilot by the name of Cornelia Fort.

This is an excerpt from a magazine article that Cornelia wrote for “The Women’s Home Companion, July 1943 issue.” It’s titled

"At the twilight's last gleaming"

Cornelia Fort's EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December, 7, 1941

"I Knew I was going to join the Women's Auxiliary

Ferry Squadron before the organization was a reality,

before it had a name, before it was anything but a radical

idea in the minds of a few men who believed that woman

could fly airplanes. But I never knew it so surely as I did

in Honolulu on December 7, 1941.

At dawn that morning I drove from Waikiki to the

John Rogers Civilian airport right next to Pearl Harbor,

where I was a civilian pilot instructor. Shortly after

six-thirty I began landing and take-off practice with my

regular student. Coming in just before the last landing, I

looked casually around and saw a military plane coming

directly toward me. I jerked the controls away from my

student and jammed the throttle wide open to pull above

the oncoming plane. He passed so close under us that our

celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to

see what kind of plane it was.

The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone

brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and

utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of

the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.

I looked quickly at Pearl Harbor and my spine tingled

when I saw billowing black smoke. Still I thought

hollowly it might be some kind of coincidence or

maneuvers, it might be, it must be. For surely, dear God .

. .

Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver

bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an

airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it

down, down and even with knowledge pounding in my

mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb

exploded in the middle of the harbor.

I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about

landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a

shadow passed over me and simultaneously bullets

spattered all around me.

Suddenly that little wedge of sky above Hickam Field

and Pearl Harbor was the busiest fullest piece of sky I

ever saw.

We counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came

flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were

washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the

island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave little

yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.

The rest of December seventh has been described

by too many in too much detail for me to reiterate. I

remained on the island until three months later when I

returned by convoy to the United States.

When I returned, the only way I could fly at all

was to instruct Civilian Pilot Training programs. Weeks

passed. Then, out of the blue, came a telegram from the

War Department announcing the organization of the

WAFS (Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron) and the

order to report within twenty-four hours if interested. I

left at once.

Because there were and are so many disbelievers in

women pilots, especially in their place in the army,.

Officials wanted the best possible qualifications to go

with the first experimental group. All of us realized

what a spot we were on. We had to deliver the goods or

else. Or else there wouldn't ever be another chance for

women pilots in any part of the service.

I have yet to have a feeling which approaches in

satisfaction that of having signed, sealed and delivered

an airplane for the United States Army. The attitude

that most nonflyers have about pilots is distressing and

often acutely embarrassing. They chatter about the

glamour of flying. Well, any pilot can tell you how

glamorous it is. We get up in the cold dark in order to

get to the airport by daylight.

None of us can put into words why we fly. It is something

different for each of us. I can't say exactly

why I fly but I know why as I've never known anything in my life.

I know it in dignity and self-sufficiency and in the pride of skill. I know it in the satisfaction of usefulness.

I, for one, am profoundly grateful that my one talent, my

only knowledge, flying, happens to be of use to my country

when it is needed. That's all the luck I ever hope to have."

Cornelia Fort was Stationed at the 6th Ferrying Group base at Long Beach, California, and on March 21, 1943 she became the first woman in American history to die while serving on active military duty. At the time of the her death, , Cornelia Fort was one of the most accomplished pilots of the Women Airforce Service Pilots.

The footstone of her grave is inscribed, "Killed in the Service of Her Country."

She was 24 years old.

Her sister described her as "A great rebel of her time." – I’d call her a true American Hero!

.... Dee Jae

I have always had a special interest in World War II for some reason. Maybe it’s a reincarnation thing and I lived another life during that era. What ever the reason, I was especially fascinated during the years that I lived in Germany and visited the landmark sites where so much of that war had occurred.

I usually like to end the show with information on women in history, but given what a historic day this is, I decided to switch things up and open the show with women in history.

December 7th is Pearl Harbor Day. As President Roosevelt called it, “A day that would live in infamy”. On December 7, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor Hawaii. the attack started at 7:48 a.m. Hawaiian Time. 90 minutes after the attack began, it was over. And 2,386 Americans were dead and 1,139 had been wounded. It was equivalent to 9/11. Unexpected and devastating.

Lt. Annie G. Fox served as the chief nurse in the Army Nurse Corps at Hickam Field during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

And she was the first woman in history to receive the Purple Heart for combat service for her role in coordinating treatment of the wounded that day.

It was the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II.

But there was also another woman who was at Pearl Harbor on that infamous day. A pilot by the name of Cornelia Fort.

This is an excerpt from a magazine article that Cornelia wrote for “The Women’s Home Companion, July 1943 issue.” It’s titled

"At the twilight's last gleaming"

Cornelia Fort's EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December, 7, 1941

"I Knew I was going to join the Women's Auxiliary

Ferry Squadron before the organization was a reality,

before it had a name, before it was anything but a radical

idea in the minds of a few men who believed that woman

could fly airplanes. But I never knew it so surely as I did

in Honolulu on December 7, 1941.

At dawn that morning I drove from Waikiki to the

John Rogers Civilian airport right next to Pearl Harbor,

where I was a civilian pilot instructor. Shortly after

six-thirty I began landing and take-off practice with my

regular student. Coming in just before the last landing, I

looked casually around and saw a military plane coming

directly toward me. I jerked the controls away from my

student and jammed the throttle wide open to pull above

the oncoming plane. He passed so close under us that our

celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to

see what kind of plane it was.

The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone

brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and

utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of

the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.

I looked quickly at Pearl Harbor and my spine tingled

when I saw billowing black smoke. Still I thought

hollowly it might be some kind of coincidence or

maneuvers, it might be, it must be. For surely, dear God .

. .

Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver

bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an

airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it

down, down and even with knowledge pounding in my

mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb

exploded in the middle of the harbor.

I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about

landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a

shadow passed over me and simultaneously bullets

spattered all around me.

Suddenly that little wedge of sky above Hickam Field

and Pearl Harbor was the busiest fullest piece of sky I

ever saw.

We counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came

flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were

washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the

island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave little

yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.

The rest of December seventh has been described

by too many in too much detail for me to reiterate. I

remained on the island until three months later when I

returned by convoy to the United States.

When I returned, the only way I could fly at all

was to instruct Civilian Pilot Training programs. Weeks

passed. Then, out of the blue, came a telegram from the

War Department announcing the organization of the

WAFS (Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron) and the

order to report within twenty-four hours if interested. I

left at once.

Because there were and are so many disbelievers in

women pilots, especially in their place in the army,.

Officials wanted the best possible qualifications to go

with the first experimental group. All of us realized

what a spot we were on. We had to deliver the goods or

else. Or else there wouldn't ever be another chance for

women pilots in any part of the service.

I have yet to have a feeling which approaches in

satisfaction that of having signed, sealed and delivered

an airplane for the United States Army. The attitude

that most nonflyers have about pilots is distressing and

often acutely embarrassing. They chatter about the

glamour of flying. Well, any pilot can tell you how

glamorous it is. We get up in the cold dark in order to

get to the airport by daylight.

None of us can put into words why we fly. It is something

different for each of us. I can't say exactly

why I fly but I know why as I've never known anything in my life.

I know it in dignity and self-sufficiency and in the pride of skill. I know it in the satisfaction of usefulness.

I, for one, am profoundly grateful that my one talent, my

only knowledge, flying, happens to be of use to my country

when it is needed. That's all the luck I ever hope to have."

Cornelia Fort was Stationed at the 6th Ferrying Group base at Long Beach, California, and on March 21, 1943 she became the first woman in American history to die while serving on active military duty. At the time of the her death, , Cornelia Fort was one of the most accomplished pilots of the Women Airforce Service Pilots.

The footstone of her grave is inscribed, "Killed in the Service of Her Country."

She was 24 years old.

Her sister described her as "A great rebel of her time." – I’d call her a true American Hero!

.... Dee Jae

RSS Feed

RSS Feed